I spent a lot of time on the Supreme Court in my last post. I even defended the dual free-speech cases decided on Monday. However, today, the Roberts court showed the new direction of the court and suggested what impact it will have on American society and economy.

As you may know, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor stepped down from the court last year and with the simultaneous death of Chief Justice Rehnquist, Bush appointed two new conservative justices, Alito and Robert

s. O'Connor long served as the moderate swing vote on the court. She was appointed to the court despite not having strong conservative credentials by Ronald Reagan because she was the best conservative woman Reagan could find after he promised to appoint a woman to the court in a 1980 campaign pledge. O'Connor, who leaned conservative in many of her decisions, would often side with her liberal colleagues in somewhat random cases (most famously those involving abortion and affirmative action). With O'Connor gone, Bush replaced her with more steadfast conservatives. I should mention that both Roberts and Alito are competent judges, unlike Thomas, and were reasonable choices, unlike Meyers, given that everyone knew that Bush was going to appoint conservatives. It is not that Bush picked bad judges, it's that he, as a conservative, chose conservative judges. Now we live in a country where our laws are interpreted by appointments of a political ideology, conservatism, that our nation v

s. O'Connor long served as the moderate swing vote on the court. She was appointed to the court despite not having strong conservative credentials by Ronald Reagan because she was the best conservative woman Reagan could find after he promised to appoint a woman to the court in a 1980 campaign pledge. O'Connor, who leaned conservative in many of her decisions, would often side with her liberal colleagues in somewhat random cases (most famously those involving abortion and affirmative action). With O'Connor gone, Bush replaced her with more steadfast conservatives. I should mention that both Roberts and Alito are competent judges, unlike Thomas, and were reasonable choices, unlike Meyers, given that everyone knew that Bush was going to appoint conservatives. It is not that Bush picked bad judges, it's that he, as a conservative, chose conservative judges. Now we live in a country where our laws are interpreted by appointments of a political ideology, conservatism, that our nation v oted for (sort of, when considering that the 2000 Florida recount was stopped by a 5-4 decision in the Supreme Court). The two cases decided today give us a glimpse to what conservativism at the last court in the land means for America.

oted for (sort of, when considering that the 2000 Florida recount was stopped by a 5-4 decision in the Supreme Court). The two cases decided today give us a glimpse to what conservativism at the last court in the land means for America.In two joint cases, Parents v. Seattle and Meredith v. Jefferson, white parents sued their school district for using race to assign which schools students could attend. In Meredith, the child was unable to transfer to another school for kindergarten because only minority (in KY this means black) students were being allowed in since the school did not meet a district mandated 15% nonwhite student body. A similar complaint was brought in the Seattle case, which involved another district law that high schools could not drift more than 15 percentage points away from the district's overall makeup (60% of the students in the district are nonwhite.)

In today's decision, in a predictable 5-4 vote, the supreme court invalidated school assignment plans that take race into account. Ironically using Brown as precedence, the court decided that using race to place students in different schools was a violation of the 14th amendment. This means America will finally have racial equality, right?

Not quite. First, we must ask ourselves, why do districts have these placement systems in the first place

? Brown ended the practice of official segregation of public schools. Previous to Brown, no matter what neighborhood a child lived in, or even if they lived across the street from the school, black kids went to black schools and white kids went to white schools. Brown forced districts across the country to end such practices. Since the decision, however, except in the big cities where groups were hyper-segregated, residential segregation has increased. This is largely a result of white flight to the suburbs away from the ghettoizing and darkening inner-cities. As America became more residentially segregated, its school system came to reflect it. Now instead of going across town to go to the black school, black students walk to their neighborhood dilapidated school while white students drive luxury cars to their suburban white school. I'm being hyperbolic, but this was the way America reacted to Brown. Of course, many people who left the city for the suburb with the intention of getting their kids into the "white" school did so not because they were racist, but because they wanted their kids to be in good schools and they wanted to leave a poorer neighborhood before it became run-down. This is something that every family wants, it's just that the white families had the resources to actually do it. The result was schools with incredible inequalities in the racial profile of the students and the school-funding not just in the same area, but within the same school district. Thus, in the late 1960s, federal courts began forcing districts to first deal with the vast inequality in school funding and then with the growth of highly segregated schools.

? Brown ended the practice of official segregation of public schools. Previous to Brown, no matter what neighborhood a child lived in, or even if they lived across the street from the school, black kids went to black schools and white kids went to white schools. Brown forced districts across the country to end such practices. Since the decision, however, except in the big cities where groups were hyper-segregated, residential segregation has increased. This is largely a result of white flight to the suburbs away from the ghettoizing and darkening inner-cities. As America became more residentially segregated, its school system came to reflect it. Now instead of going across town to go to the black school, black students walk to their neighborhood dilapidated school while white students drive luxury cars to their suburban white school. I'm being hyperbolic, but this was the way America reacted to Brown. Of course, many people who left the city for the suburb with the intention of getting their kids into the "white" school did so not because they were racist, but because they wanted their kids to be in good schools and they wanted to leave a poorer neighborhood before it became run-down. This is something that every family wants, it's just that the white families had the resources to actually do it. The result was schools with incredible inequalities in the racial profile of the students and the school-funding not just in the same area, but within the same school district. Thus, in the late 1960s, federal courts began forcing districts to first deal with the vast inequality in school funding and then with the growth of highly segregated schools.In one such decision in 1971, Serrano v. Priest, the supreme court ruled that districts had to equally distribute property tax funds (which were primarily used to fund public schools) across the whole district. Previously, property taxes were given to the school that served the neighborhood, resulting in richer neighborhoods having much wealthier schools. It shouldn't have come as a surprise when items like Proposition 13 sprung up to solve the problem by slashing property taxes (leaving school funding mostly to the state and "voluntary donations," which of course disproportionately came from richer neighborhoods and COULD be given to individual schools).

With such persistent inequalities in wealth within school districts came equally insistent inequities in student body make up. Within some districts, better schools were about 90% white, while worse schools were 90% minority. When such a district crossed some threshol

d and became what a federal court called 'segregated' they either took over the district or court ordered it to rectify the problem. Often the solution was forced busing. Ironically, forced busing placed students in a position they were before Brown--of being bused across town to a school far away when they may have lived across the street from a better school--except now it was done in the name of desegregation rather than segregation. Since the practice was so unpopular for a variety of reasons, school districts sought means to achieve the same ends that would be less unpopular with parents. One way, which was used in the high school I attended, was to start magnet programs in inner-city schools, thus putting more funds in poorer schools and attracting students of a different racial (and economic) make up into the school voluntarily. The other, which is

d and became what a federal court called 'segregated' they either took over the district or court ordered it to rectify the problem. Often the solution was forced busing. Ironically, forced busing placed students in a position they were before Brown--of being bused across town to a school far away when they may have lived across the street from a better school--except now it was done in the name of desegregation rather than segregation. Since the practice was so unpopular for a variety of reasons, school districts sought means to achieve the same ends that would be less unpopular with parents. One way, which was used in the high school I attended, was to start magnet programs in inner-city schools, thus putting more funds in poorer schools and attracting students of a different racial (and economic) make up into the school voluntarily. The other, which is what these supreme court decisions are all about, was preventing transfers to wealthier schools by white students and placing more white students in predominantly non-white schools if those schools were reasonably close by. For example, I live on the outskirts of my city and all four high schools are in the center of the city and in relatively close proximity. Imagine that the of the four schools in my district 2 of them were predominantly white and 2 were predominantly black, the district might send me to the predominantly black one for integration purposes because all of the schools are near each other and the busing difference would not be significant. Likewise, a black student living in the center of the city might be sent to a white school, because even though he's closer to the black school, he's still pretty close to both of them. It is these kinds of tweaking of school lines and limits on transfers that have allowed districts to push towards some type of desegregation.

what these supreme court decisions are all about, was preventing transfers to wealthier schools by white students and placing more white students in predominantly non-white schools if those schools were reasonably close by. For example, I live on the outskirts of my city and all four high schools are in the center of the city and in relatively close proximity. Imagine that the of the four schools in my district 2 of them were predominantly white and 2 were predominantly black, the district might send me to the predominantly black one for integration purposes because all of the schools are near each other and the busing difference would not be significant. Likewise, a black student living in the center of the city might be sent to a white school, because even though he's closer to the black school, he's still pretty close to both of them. It is these kinds of tweaking of school lines and limits on transfers that have allowed districts to push towards some type of desegregation.With the decisions on today, schools will no longer be able to use race as a tool for preventing segregation as I described. The decision will have two effects. One, it calls into question the entire idea that schools should be desegregated. If race cannot not be taken a

ccount for school assignments, then how can a district do anything to desegregate itself. Secondly, it will force districts to find other means to solve problems of economic and racial inequality within their district. Possibly, schools could use family income rather than race to place students. Such a system has never been attempted and may simply cause richer residents (white or black) to leave the district.

ccount for school assignments, then how can a district do anything to desegregate itself. Secondly, it will force districts to find other means to solve problems of economic and racial inequality within their district. Possibly, schools could use family income rather than race to place students. Such a system has never been attempted and may simply cause richer residents (white or black) to leave the district.The decision makes it much tougher for districts to desegregate and calls into question the stated goal of desegregation. Additionally, in its argument that to 'treat races fairly we need to treat races fairly' is the seed to undue affirmative action as a whole. I'll save it for another post, but I am actually opposed to affirma

tive action. I am opposed to for a few reasons, but one main one is that I believe that the need for affirmative action can be solved through public school desegregation. We live in a world of vast racial inequality. It is with the public school system that America has its only real hope for integration of people of diverse economic and racial backgrounds. The push for such desegregation has originated with federal courts. With this decision, this will less become the case. Rich, poor, black, and white students all benefit from a diverse student body. This is not to mention the benefit it affords to a democratic society. If we cannot come together in the public school system, where will we come together. Where will the fortunate get a glimpse of America's underlcass and where will the unfortunate raise themselves out of their situation? Where will America learn more about each other than Chappellistic stereotypes (yes, I just invented the word Chappellestic)? The decision signals an to the end of a battle for America to truly achieve a color-blind society that America has long been losing.

tive action. I am opposed to for a few reasons, but one main one is that I believe that the need for affirmative action can be solved through public school desegregation. We live in a world of vast racial inequality. It is with the public school system that America has its only real hope for integration of people of diverse economic and racial backgrounds. The push for such desegregation has originated with federal courts. With this decision, this will less become the case. Rich, poor, black, and white students all benefit from a diverse student body. This is not to mention the benefit it affords to a democratic society. If we cannot come together in the public school system, where will we come together. Where will the fortunate get a glimpse of America's underlcass and where will the unfortunate raise themselves out of their situation? Where will America learn more about each other than Chappellistic stereotypes (yes, I just invented the word Chappellestic)? The decision signals an to the end of a battle for America to truly achieve a color-blind society that America has long been losing.After that peppy diatribe, let's move on to the Supreme Court's second big decision. This one is a little more complicated. To describe it in simple terms is a little misleading, but to go into the details makes it lack some of its importance. I'll try somewhere in between.

In Leegin v. PSKS, the court decided, 5-4 again, to overturn a law made in 1911 that illegalized certain price floors. For those of you who never took econ

omics (or fell asleep trying to) a price floor is a minimum price that a good can be sold for. Economics teachers drill into their students that price floors are bad, because, well, most economics teachers are neo-liberal arch-conservatives (more on this in another post) that don't know what they're talking about. But that aside, the issue here was not government enforced price floors, which economics teachers hate, but price floors agreed upon between companies, which economics teachers never talk about, because they've been illegal since 1911. The issue in this case was weather a discount retailer could sell a good less than its producer allowed. Producers don't want discounts to get to extreme in relation to their products because they fear it will upset their other sellers and it might cause a drop in their selling price. Thus, producers often make agreements with sellers that they cannot sell something for less than an advertised price. This is a notorious practice for guitar companies and is also why Ross does not usually advertise with the labels of their merchandise. Up until today, producers could not form agreements with sellers that would force them to not sell below a price floor at all. Now, this is permisible.

omics (or fell asleep trying to) a price floor is a minimum price that a good can be sold for. Economics teachers drill into their students that price floors are bad, because, well, most economics teachers are neo-liberal arch-conservatives (more on this in another post) that don't know what they're talking about. But that aside, the issue here was not government enforced price floors, which economics teachers hate, but price floors agreed upon between companies, which economics teachers never talk about, because they've been illegal since 1911. The issue in this case was weather a discount retailer could sell a good less than its producer allowed. Producers don't want discounts to get to extreme in relation to their products because they fear it will upset their other sellers and it might cause a drop in their selling price. Thus, producers often make agreements with sellers that they cannot sell something for less than an advertised price. This is a notorious practice for guitar companies and is also why Ross does not usually advertise with the labels of their merchandise. Up until today, producers could not form agreements with sellers that would force them to not sell below a price floor at all. Now, this is permisible.So, what's the big deal? For those of you who don't know your history, 1911 was the heyday of the progressive movement. One of the goals of the movem

ent was to engage in "trust busting." Trusts were basically cartels, which are basically oligopolies. In those economics classes you might have heard all about supply and demand and the beauty of the free market and all that stuff. With all that pretty stuff they would always include a little disclaimer for every economic principle that sounded something like "in a perfectly competitive market...," which is the economics equivalent of physicists "in a vacuum..." While good for simplification of formulas and ideas, it also means that everything you learn in economics and beginning physics applies to phenomenon that are almost completely absent on earth. Additionally, as you add more air resistance the equations become less and less descriptive of what you're supposed to be describing (try dropping a baseball from a tower in a hurricane), and as you lessen competition, the laws of supply and demand begin to have less and less relevance.

ent was to engage in "trust busting." Trusts were basically cartels, which are basically oligopolies. In those economics classes you might have heard all about supply and demand and the beauty of the free market and all that stuff. With all that pretty stuff they would always include a little disclaimer for every economic principle that sounded something like "in a perfectly competitive market...," which is the economics equivalent of physicists "in a vacuum..." While good for simplification of formulas and ideas, it also means that everything you learn in economics and beginning physics applies to phenomenon that are almost completely absent on earth. Additionally, as you add more air resistance the equations become less and less descriptive of what you're supposed to be describing (try dropping a baseball from a tower in a hurricane), and as you lessen competition, the laws of supply and demand begin to have less and less relevance.In a perfectly competitive market, firms will seek to lower their prices to maximize sales. As a market

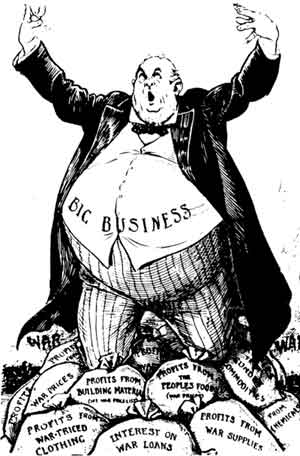

turns moves towards monopoly, the system becomes less consumer friendly. In a monopoly, firms seek to raise prices to maximize profits. Simple game theory will tell you that two competing firms, if they can come to an agreement, would both benefit from not engaging in price competition. This is good for the companies, but bad for the consumers who end up paying more to increase the company's profit margins. This is why the progressives went after businesses for engaging in oligopolistic practices like price floor. If a seller and a producer are allowed to agree on a price floor, there's little reason for preventing companies from agreeing on price floors with each other. The result would be price gouging of consumers and big profits for businesses. Should we be surprised then that the decision was made by the court's 5 conservative members. There's a reason they're there.

turns moves towards monopoly, the system becomes less consumer friendly. In a monopoly, firms seek to raise prices to maximize profits. Simple game theory will tell you that two competing firms, if they can come to an agreement, would both benefit from not engaging in price competition. This is good for the companies, but bad for the consumers who end up paying more to increase the company's profit margins. This is why the progressives went after businesses for engaging in oligopolistic practices like price floor. If a seller and a producer are allowed to agree on a price floor, there's little reason for preventing companies from agreeing on price floors with each other. The result would be price gouging of consumers and big profits for businesses. Should we be surprised then that the decision was made by the court's 5 conservative members. There's a reason they're there.So, how did we get from the progressivism of the Warren Court, to the moderate reaction of the Rehnquist Court, to the 5-4 conservatism of the Roberts Court? There's an easy answer. In between 1932 and 1968 (36 years), the years that the Warren Court was built, the Democrats held the presidency for 28 years. In between 1968 and 2008 (40 years) the Democrats have held the presidency for 12 years. It's simply probability as to when justices are forced to retire. Of course, justices usually like to step down when they think their replacement will agree with him/her, which is why Clinton was able to appoint 4 justices. Still, the dominance of Republicans at the executive level has allowed conservatives to turn the court in their favor away from the judicial philosophy of the Warren Court. The result has been and will be decisions like those announced today.

No comments:

Post a Comment